Geology

Arches National ParkSculptures by Nature

When you see the awe-inspiring arches, improbably balanced rocks, and fantastic rock formations of Arches National Park, you can’t help but wonder how they were created.

How Arches Form

The complex 300 million-year story of the formation of the rock wonders in Arches National Park features powerful tectonic movements, retreating and advancing seas, flowing salt deposits, faulting, collapse, uplift, and the forces of erosion, especially water.

Although area geologic events that came before contributed to the landscape we see today, the formation of Arches really begins to take shape 65 million years ago, when geologic forces warped and cracked deeply buried sandstone rock layers. Then about 15 million years ago, movements in the Earth’s crust caused the entire region to rise thousands of feet, not as mountains, but as an elevated surface, creating the Colorado Plateau. What had been a sea-level depositional landscape where sediments accumulated became a high-elevation erosional landscape where water and gravity continually draw material to lower elevation areas.

Over time, rivers and their tributaries removed vast amounts of overlying sediment and rock, until the cracked sandstone rock layers were exposed. Water then seeped into the cracks further eroding the rock, creating parallel sandstone fins. Rain and the freeze and thaw cycle continued to erode the fins into arches.

Today, water continues to shape the landscape. Rain erodes the rock and carries sediment down washes and canyons to the Colorado River. In winter, snowmelt pools in fractures and other cavities, then freezes and expands, breaking off chunks of sandstone. Small recesses develop and grow bigger with each storm.

The Walls Come Tumbling Down (eventually)

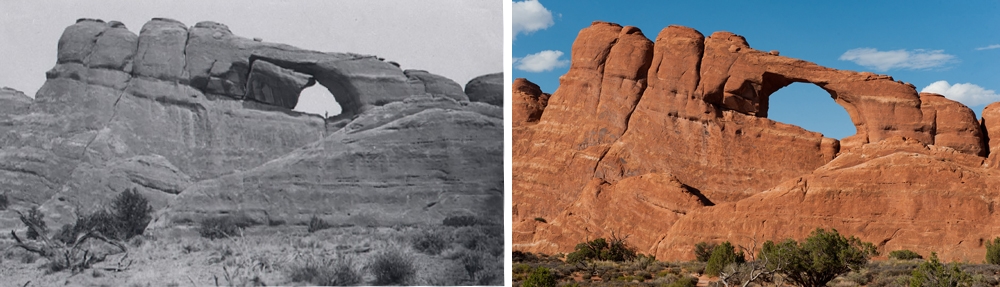

Although it seems like the arches will stand forever, they will not. Eventually, the same forces that created the formations of Arches National Park will cause them to collapse. Usually, geologic changes occur very slowly, but quick and dramatic changes sometimes occur.

In 1940, a large boulder suddenly fell out of Skyline Arch, roughly doubling the size of the opening. The span is now 71 feet (21.6 m) across and 33.5 feet (10.3 m) wide.

Then, on August 4, 2008, Wall Arch, along the popular Devils Garden Trail collapsed during the night. No one saw the collapse and thankfully no one was injured. Wall Arch was the 12th largest free-standing arch in the park with a span of 71 feet (21.6 m).

Wall Arch before and after its collapse in 2008 – NPS photos

Types of Arches

There are over 2,000 natural stone arches in Arches National Park, and countless other openings in the rocks. So, what classifies an opening in the rock as an arch? To be an official arch, a span must have a light opening of at least three feet in one direction.

Freestanding Arch

A freestanding arch stands on its own and is not part of another rock wall, cliff, or fin. Some are referred to as “windows” for the scenic views they frame.

Delicate Arch, Landscape Arch, North and South Windows, and Double Arch are examples of freestanding arches.

Pothole Arch

This type of arch forms when a pothole (small depression) on top of a rock mass merges with an alcove on a rock face. The light opening is often smooth and rounded at the top, casting light down into a room-shaped opening below.

Examples include the aptly-named Pothole Arch Upper and Lower near Garden of Eden and Bean Pot Arch in the Great Wall.

Cliff Wall Arch

This type of arch is on the side of or adjacent to rock walls or cliffs. They can be more difficult to spot, since the light opening is often only visible when you stand under the arch and look up.

Examples include Park Avenue Arch, Biceps Arch in The Windows Section, and Visitor Center Arch.

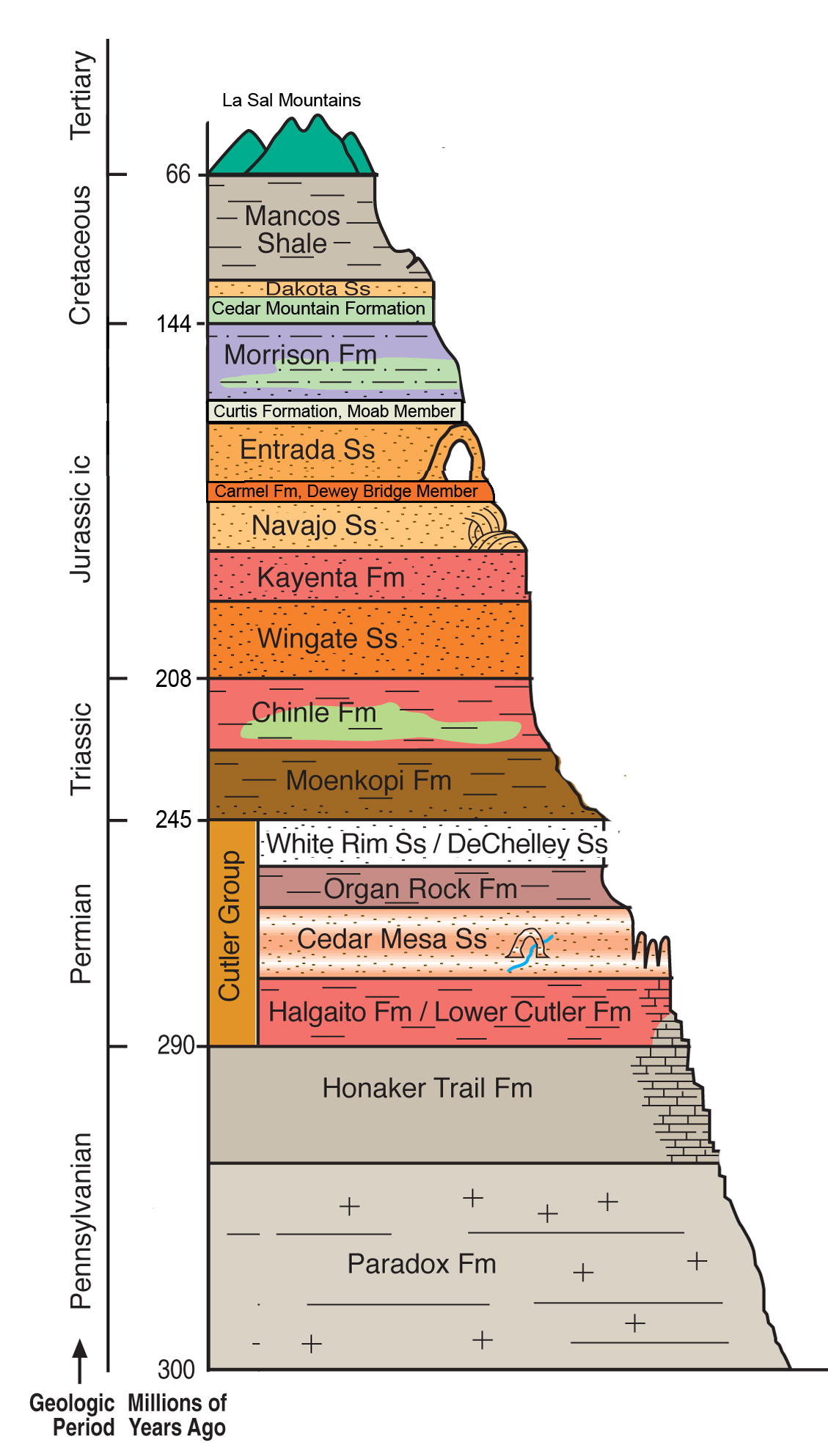

Common Strata of the Canyonlands Region

This sequence shows the rock layers in the Canyonlands region, from youngest at the top to the oldest at the bottom.

Some layers shown here are not found within Arches National Park, but are visible from locations near the park boundary, such as the visitor center.

The most dominant rock layers at Arches are the Navajo Sandstone, Dewey Bridge, and Entrada Sandstone.

Why are the Rocks Red?

Minerals in the rock are most often the common reason for a rock’s color. Iron-rich sediments exposed to oxygen before being lithified (turned to stone), can make rock any shade of yellow, orange, or red. Rock formed from sediments deposited in a oxygen-poor environment, such as in deep water, will tend to be gray, green or black.

Your purchases and donations support education and research on the public lands of Southeastern Utah!

Arches & Canyonlands Geological Bandana

15.99 (15% off for members)

Arches To Zion Geology Guide

16.99 (15% off for members)

Geologic Map of Arches National Park

14.99 (15% off for members)

Landscapes of Utah's Geologic Past

14.99 (15% off for members)

Utah Geologic Highway Map

10.95 (15% off for members)